For the past two years, reports have trickled in from around the country of car thieves appearing to break into vehicles using a mystery device that mimicked the vehicle’s key fobs. Last year in Long Beach, Calif., police even caught them on camera, as shown above. Yet such events provoked more questions than answers; police knew nothing about the devices, and neither did carmakers.

Today, the problem took a step out of the shadows, with a warning from the insurance industry that such break-ins are becoming more common — even as experts still puzzle over how it’s possible.

The National Insurance Crime Bureau, a not-for-profit fraud prevention unit paid for by insurance companies, said Wednesday that it had seen a spike in thefts of property from cars due to scanner boxes that can unlock vehicles with keyless entry systems.

“Our law enforcement partners tell us they are seeing this type of criminal activity and have recovered some of the illegal devices,” said NICB President and CEO Joe Wehrle in a statement.

The NICB didn’t detail how many such cases it had counted, but reports have surfaced in California, Illinois and elsewhere of the technology being used.

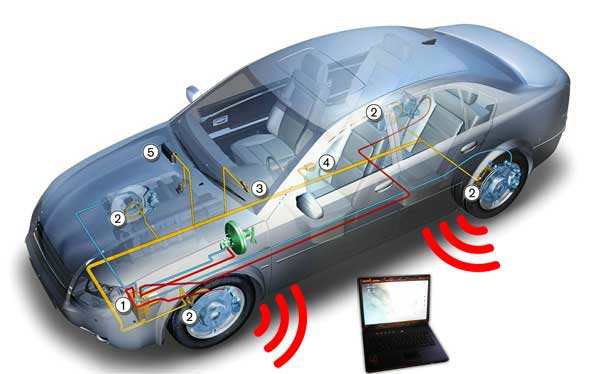

How could such thefts happen? Security researchers have detailed several holes and hacks for the transmission system between a key fob and a vehicle used by carmakers around the world; in theory, the fob and car are supposed to broadcast a unique encripted code every time the fob’s used to lock and unlock the car. Over the past several years, security researchers have demonstrated several hacks aimed at disrupting that transmission and tricking the car into opening its doors.

But to date, all of the publicized hacks have either involved complicated surveillance — essentially stealing a code from the key fob then later replaying it to the car — or equipment that’s not portable. As reported by Wired, an Australian hacker will demonstrate a car key-hacking exploit later this week using about $1,000 in equipment he built in his living room which he says works on multiple types of vehicles, but is still far removed from the handheld devices on the streets.

At the moment, the savvy burglers have not advanced beyond petty theft of goods inside a vehicle; the security built into keyless fobs for starting a vehicle has not been shown to be vulnerable to hacking to date. Brute-force thefts are still the most common, and a few theft rings have been busted using keys programmed with codes stolen from dealerships. (Given that the NICB says a third of car break-ins involve vehicles left unlocked by their owners, simply remembering to lock your car would seem to be a good first step.)

But computer security experts have long raised alarms about the increasing reliance of vehices on computer code — from navigation systems to self-driving features and steer or brake-by-wire controls — and what hackers could do if they had physical access to a car’s ports. In the neverending battle between cops and robbers, the black hats have a small but worrying advantage.